The tick’s ability to survive through inclement weather has been one of the keys to its proliferation over the years. One mistake many people make, especially during the winter months, is thinking that ticks can’t survive freezing temperatures. As a result, on a warmer winter day, they let their guard down and put themselves at risk for a tick encounter.

Our prior blog posts talk about the tick lifecycle which on average is about two years. This means that ticks in the winter climates still find a way to survive, even during spells of below-zero temperatures.

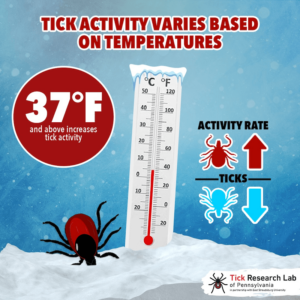

Biologically speaking, ticks and other cold-blooded creatures don’t hibernate. Rather, they go into a low-energy stage. This means that, as soon as temperatures rise above freezing, even if it’s just for a one or two-day spell in the middle of winter, some ticks who have yet to feed can remobilize and resume questing for a blood meal. Of course, this is more likely if the ground is thawed and the ticks aren’t covered by snow.

One of the tick’s most crucial survival mechanisms, especially during the winter months, is its ability to withstand extremely low temperatures. Researchers from Miami University of Ohio and Ohio State University performed a study where they chilled species of ticks at a constant rate while monitoring their body temperatures. Through their experiment, they identified two cold-weather thresholds, a lower lethal temperature and the supercooling point. Lower lethal temperature is the temperature that causes 50% mortality in a population, and the supercooling point is the temperature at which the tissues freeze. For the Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes scapularis), researchers found that some of them died at the lower lethal temperature (-10o C / 14o F), but some were able to survive all the way to -21.7oC / -7.06oF by drawing water out of their cells before it crystallized. The lower lethal limits for the ticks examined were high compared to their supercooling point, indicating that chilling can cause mortality however; some ticks can survive past the lethal limit to temperatures of -7oF.

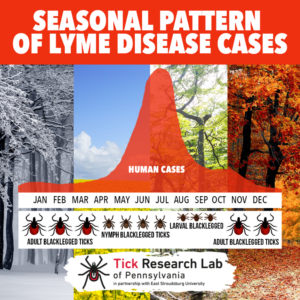

Aside from the occurrence of cold weather extremes, one of the most important factors in determining how active a tick will remain in the winter is whether it had a blood meal before freezing temperatures set in. After all, the blood meal is the sustenance which enables ticks to evolve to subsequent lifecycles. For ticks in the earlier larval and nymph stages who have yet to feed, the onset of winter likely means they will remain inactive until temperatures rise above freezing. On the other hand, unfed ticks in the adult lifecycle stage can summon the strength needed to resume questing when the cold weather recedes, even if it’s just for a day or two. Additionally, ticks feed on warm-blooded creatures, further enabling them to be active even when temperatures are extremely cold.

From an environmental standpoint, ticks’ most adverse landscapes are sunny, dry and arid in nature. Conversely, shade and moisture, two of ticks’ most favorable environmental conditions, are present during the northeast winter months. Additionally, the abundance of leaf litter from the fall season provides suitable nests. Ticks in the larval and nymph stages who have fed will use this time to begin evolving to the next lifecycle stage, while adult female ticks who have fed will begin converting their blood meal into eggs that they will lay in the spring.

The final thing worth noting is the effect of changing temperatures on tick populations. With warmer winter temperatures, ticks can survive through the shorter winter months. In addition, due to warmer temperatures, common tick carrying hosts like white-tailed deer and the white-footed mouse are increasing their home range north and south which enable ticks to expand in new areas by hitching a ride. Therefore, people who in the past may not have had to exercise the type of vigilance necessary to protect them from tick encounters, will now have to be more proactive in protecting themselves, their families, and their pets.

https://tickencounter.org/tick_notes/winter_tick_activity

https://tickencounter.org/tick_notes/polar_vorticks

https://www.adk.org/ticks-in-winter-ostfeld/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6723576/

Burks, C.S., R.J. Stweart, G. Needham and R. E. Lee, 1996; Cold hardiness in the ixodid ticks (Ixodidae), In: Acarology IX: Vol. 1, Proceedings, ed R. Mitchell, D.J. Horn, G.R. Needham and W.C. Welbourn, Ohio Biological Survey, Columbus Ohio. pp 85-87